Friday, February 9, 2024

Old Alabama Stuff : A Battle House Hotel Menu from 1857

Friday, October 20, 2023

Lola Montez Visits Mobile in 1852

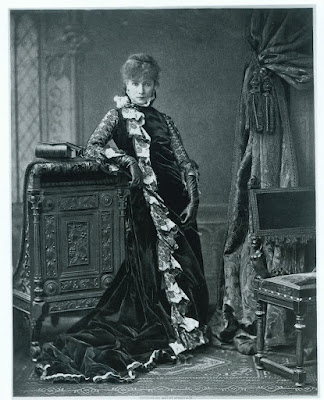

Lola Montez in 1851

In the first half of the nineteenth century "Lola Montez" was a famous--and notorious--dancer and actress who performed in Europe, the United States and elsewhere. She was born in Ireland on February 17, 1821, as Eliza Rosanna Gilbert. At the age of 16 she eloped to India with Thomas James, a lieutenant who became her first husband. They separated five years later, and Gilbert began her professional dancing career as Lola Montez.

In her short life Montez would have two other husbands and numerous lovers. That group included King Ludwig I of Bavaria, who gave her the title Countess of Landsfeld. In 1848 revolutions began in the German states, and Montez fled for Austria, Switzerland, France, London, and then America. She supported herself by dancing as she had earlier under the name Lola Montez.

Her career declined in the later 1850s. After a failed tour of Australia in 1855 and 1856, she returned to the U.S. by way of San Francisco. Further U.S. tours were unsuccessful, and she spent her final years in rescue work among "fallen" women and lecturing on morality. Montez died of syphilis on January 17, 1861, a month short of her 40th birthday, and was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

At the height of her fame she descended upon Mobile in December 1852. The Port City was not very large at the time, but had a lively performing arts scene and was a perfect stop for entertainers or theatrical companies appearing on tour in Charleston, South Carolina and New Orleans. Thus Mobile attracted Montez after appearances in Charleston that year.

Her venue was the Mobile Theatre, opened in 1841 and being operated at that time by Joseph Field, an actor, writer and theatrical manager. I've written about one of his publications, The Drama in Pokerville [1847], some of which is set in Wetumpka. Local newspapers expressed some trepidation about the appearance of Montez, but her visit was also highly anticipated. The Mobile Daily Register declared that "...the terror of the Jesuits, the favorite of an Emperor, and the cynosure of all eyes; will make her appearance on the Mobile state tomorrow evening...already we are impatient." Because of her lifestyle and her for-the-times erotic dancing, Montez was a controversial figure, but that didn't seem to prevent many people from attending her performances.

The arrival of Montez by the steamer Louisa was delayed, which no doubt increased the local anticipation. She gave six performances from December 21 and 28. Despite selling out the theater, Montez and Field had entertainment competition in Mobile. Horse races continued at the Trotting Club and Dan Rice's Hippodrome featured minstrel shows, circus acts and a parody of Hamlet.

The December 21 crowd included "a large number of highly enthusiastic ladies" who watched Montez in her "Sailor's Dance" and "Spider Dance". These performances came between various comedies from the theater's regular company. After two night of dances, a third night on December 23 featured "Lola Montez in Bavaria" with the lady enacting scenes from her own life. Christmas Eve repeated the drama, but added "Sailor's Dance".

On Christmas Day she played the title role in Maritana with Joseph Field as the male lead. Maritana was an opera written by William Vincent Wallace and first performed in London in 1845. Her final appearance on December 28 repeated "Lola Montez in Bavaria" and added the dance "La Saviglliana". On that final night the enthusiastic audience convinced her to repeat the dance. In a curtain call Montez expressed her appreciation of the response to her by audiences in Mobile. She left the city and arrived in New Orleans on New Year's Eve.

I want to express my appreciation to Sara Elizabeth Gotcher whose dissertation cited below provided many details and newspaper quotes about Montez's appearance in Mobile.

FURTHER READING

Burr, C. Chauncey. Autobiography of and Lectures by Lola Montez [1860]

Gotcher, Sara Elizabeth. "The Career of Lola Montez in the American Theatre" PhD dissertation, LSU, 1994

Morton, James, Lola Montez: Her Life & Conquests, Portrait, 2007

Seymour, Bruce, Lola Montez, a Life, Yale University Press, 1996

Photo by Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon

Friday, June 30, 2023

Alabama Photos: A Mobile Youth Orchestra in 1937

I found the first photograph below in D. Antoinette Handy's Black Women in American Bands and Orchestras [1981]. Then I found it and a related photo at a web site devoted to the history of America's New Deal during the Great Depression. The photos show a girls' orchestra performing in Mobile under the auspices of the National Youth Administration. Let's investigate.

President Franklin Roosevelt signed an executive order creating the National Youth Administration in June 1935 and it operated as part of the Works Progress Administration until 1939. The NYA was discontinued in 1943 as the economic effects of World War II began to take effect. The agency paid grants to young people aged 16 to 25 to assist with job training and actual jobs in public works and service projects. That web site on the New Deal I mentioned has some detail from the NYA's final report about the orchestras sponsored by the agency.

There is another important Alabama connection at the NYA. The agency's Executive Director for its entire existence was Aubrey Willis Williams, who was born in Springville in St. Clair County on August 23, 1890. Despite his impoverished background, by the time he was 30 he had earned a PhD at the University of Bordeaux in France and begun a career in social work in Ohio and Wisconsin. President Roosevelt appointed him as Assistant Federal Relief Administrator under Harry Hopkins, an important New Deal figure and a close advisor to FDR.

When the National Youth Administration was organized, Roosevelt selected Williams to direct it. One of his early tasks required him to appoint a Youth Director for each of the 48 states; he picked future president Lyndon Baines Johnson to head the operation in Texas. The 26 year-old Johnson soon earned a reputation for fairness that included black participation in the agency's programs. This experience may have influenced President Johnson's Great Society programs and efforts such as Job Corps and Upward Bound.

In 1945 after the NYA had been dissolved, Roosevelt appointed Williams to be director of the Rural Electrification Administration. His support of blacks in federal programs meant that Southern senators did not support him and blocked his nomination.

He returned to Alabama to continue civil rights work, but attacks by Southern politicians who wanted to link integration and communism continued. These men included the powerful senator from Mississippi James Eastland and Governor George Wallace.

In 1945 Williams and Alabama journalist Gould Beech had purchased The Southern Farmer newspaper and turned it into a venue for liberal opinion and activity in the South. The paper eventually failed, and Williams returned to Washington, D.C., in the early 1960s. Despite suffering from stomach cancer, he attended Martin Luther King, Jr.'s March on Washington in August 1963. Williams died on March 15, 1965.

Aubrey Willis Williams [1890-1965]

Source: Library of Congress via Wikipedia

Friday, September 23, 2022

Dr. Margaret Cleaves Dies in Mobile in 1917

During her lifetime Margaret Abigail Cleaves became a well-known physician and medical researcher in the United States. Today she is largely forgotten, a footnote in medical history. I recently stumbled on a connection to Alabama, so let's investigate.

Cleaves was born on November 25, 1848, in Columbus City, Iowa; she was the third of seven children in the family. Her father John was a physician, and as a child she traveled with him on his rounds. She graduated from a public high school at 16 and taught in public schools until 1870, when she decided to study medicine. She finished her M.D. at the Iowa State University Medical Department in 1873.

In her career she practiced in several states: Iowa, Illinois, Pennsylvania and beginning in 1890 in New York City. In 1883 she left the U.S. to spend almost two years in Scotland, England, France, Italy, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Belgium. Cleaves visited asylums for the insane as well as attending lectures and general hospital clinics.

Cleaves was a prolific researcher, organizer and author in addition to her clinical work. Some 40 of her publications are indexed in the National Library of Medicine's IndexCat database to older medical literature, 1880-1961. They range from 1886 to 1908, with most published in the 1893-1907 period. Those articles describe her work with electrotherapy, phototherapy, radium and conditions in various asylums. Her Wikipedia entry describes her seminal 1903 publication describing the use of radium to treat uterine cervix cancer.

Among her many organizational achievements was the development of the New York Electro-Therapeutic Clinic, Laboratory and Dispensary in New York City. There she did research and treated numerous male and female neurasthenia patients. Her final publication seems to have been the 1910 book noted below.

Various sources agree that Cleaves died in Mobile in early November, 1917. Wikipedia says November 7; the article below based on information from two of her sisters has November 13. The 1920 American Medical Biographies entry on Cleaves has the November 7 date and a further note that she died in a Mobile hospital. "Alabama Deaths & Burials Index 1881-1974" via Ancestry.com gives the date as 13 Nov 1917, her age as 69.

None of the sources I've examined have anything on Cleaves' professional activities after the 1910 book noted below. What did she do in those years, besides remaining in New York, and why did she end up in Mobile? Questions for further research...

In the 1900 U.S. Census, Cleaves appears, renting in what is presumably a boarding house at 79 Madison Avenue with a number of other individuals. According to what I found at Ancestry.com, she appears in various city directories for NYC between 1891 and 1915. Some of the addresses were also along Madison Avenue. That north-south street in Manhattan did not become associated with the advertising industry until the 1920's.

Cleaves has a Find-A-Grave entry, but no burial location is listed. There is a long biographical note from Woman of the Century. Parents and two sisters are buried in Columbus City Cemetery, Columbus City, Iowa. Her sister Jennie, who died in 1919, was the only one of those to outlive Margaret. Apparently Cleaves never married.

Margaret Abigail Cleaves, M.D. [1848-1917]

Source: Willard, Frances Elizabeth (1893) A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life, Moulton via Wikipedia

Source:

Rock Island Argus [Rock Island, Ill.] 16 November 1917 via Chronicling America

This book is available via the Internet Archive.

Also available at the Internet Archive is this 890-page book

Friday, February 11, 2022

Sarah Bernhardt Visits Mobile, Alabama in 1881

Source: Engines of Our Ingenuity

ready laid tried to get it in through the door. But this was impossible. Nothing could be more comical than to see those unfortunate servants adopt every expedient."

Credit...Harvard Theater Collection, Houghton Library, Cambridge, Mass.

In 1896

CHAPTER XXIX

FROM THE GULF TO CANADA AGAIN

e arrived at Cincinnati safe and sound. We gave three performances there and set off once more for New Orleans. Now, I thought, we shall have some sunshine and we shall be able to warm our poor limbs, stiffened with three months of mortal cold. We shall be able to open our windows, and breathe fresh air instead of the suffocating and anæmia-giving steam heat. I fell asleep and dreams of warmth and sweet scents lulled me in my slumber. A knock at my door roused me suddenly, and my dog with ears erect sniffed at the door, but as he did not growl I knew it was some one of our party. I opened the door and Jarrett, followed by Abbey, made signs to me not to speak. Jarrett came in on tiptoes and closed the door again.

“Well, what is it now?” I asked.

“Why,” replied Jarrett, “the incessant rain during the last twelve days has swollen the river to such a height that the bridge across the bay of St. Louis threatens to give way. If we go back we shall require three or four days.”

I was furious. Three or four days and to go back to the snow again. Ah, no, I felt I must have sunshine!

“Why can we not pass? Oh, heavens, what shall we do!” I exclaimed.

“Well, the engine driver is here. He thinks that he might get across, but he has only just married, and he will try the crossing on condition that you give him $2,500, which he will at once send to Mobile where his father and wife live. If we 429get safely to the other side he will give you back this money, but if not it will belong to his family.”

“Yes, certainly, give him the money and let us cross.”

As I have said, I generally traveled by special train. This one was made up of only three carriages and the engine. I never doubted for a moment as to the success of this foolish and criminal attempt, and I did not tell anyone about it except my sister, my beloved Guérard, and my faithful Félicie and her husband Claude. The comedian, Angelo, who was sleeping in Jarrett’s berth on this journey, knew of it, but he was courageous and had faith in his star. The money was handed over to the engine driver who sent it off to Mobile. It was only just as we were actually starting that I had the vision of the responsibility I had taken upon myself, for it was risking without their consent the lives of twenty-seven persons. It was too late then to do anything, the train had started and at a terrific speed it touched the bridge. I had taken my seat on the platform and the bridge bent and swayed like a hammock under the dizzy speed of our wild course. When we were half way across it gave way so much that my sister grasped my arm and whispered: “Ah, we are drowning!” I certainly thought as she did that the supreme moment had arrived.

My last minute was not inscribed, though, for that day in the Book of Destiny. The train pulled itself together and we arrived on the other side of the water. Behind us we heard a terrible noise. The bridge had given way. For more than a week the trains from the East and the North could not enter the city.

I left the money to our brave engine driver but my conscience was by no means tranquil and for a long time my sleep was disturbed by the most frightful nightmares.

When getting out of the train I was more dead than alive. I had to submit to receiving the friendly but fatiguing deputation of my compatriots. Then, loaded with flowers, I climbed into the carriage that was to take me to the hotel. The roads were rivers and we were on an elevated spot. The lower part 430of the city, the coachman explained to us in Marseilles French, was inundated up to the tops of the houses. The negroes had been drowned by hundreds. “Ah, hussy!” he cried as he whipped up his horses. At that period the hotels in New Orleans were squalid—dirty, uncomfortable, black with cockroaches, and as soon as the candles were lighted, the bedrooms became filled with large mosquitoes that buzzed around and fell on one’s shoulders, sticking in one’s hair. Oh, I shudder still when I think of it!

At the same time there was an opera company in the city, the “star” of which was a charming woman, Emilie Ambre, who at one time came very near being Queen of Holland. The country was poor, like all the other American districts where the French were to be found preponderating. Ah, we are hardly good colonists!

The opera did a very poor business and we did not do excellently, either. Six performances would have been ample in that city; we gave eight.

Nevertheless, my sojourn pleased me immensely. An infinite charm was evolved from it. All these people, so different, black and white, had smiling faces. All the women were graceful. The shops were attractive from the cheerfulness of their windows. The open-air traders under the arcades challenged one another with joyful flashes of wit. The sun, however, did not show itself once. But these people had the sun within themselves.

I could not understand why boats were not used. The horses had water up to their hams, and it would have been impossible even to get into a carriage if the pavements had not been a meter or more high.

Floods being as frequent as the years, it would be of no use thinking of banking up the river or arm of the sea. But walking was made easy by the high pavements and small, movable bridges. The dark children amused themselves catching crayfish in the streams. Where did they come from? And they sold them to passersby. Now and again, we would see a whole family of water serpents speed by. They swept along 431with raised head and undulating body like long, starry sapphires.

I went down toward the lower part of the town. The sight was heartrending. All the cabins of the colored inhabitants had fallen into the muddy waters. They were there in hundreds squatting upon these moving wrecks, with eyes burning from fever, their white teeth chattering. Right and left, everywhere, were dead bodies floating about, knocking up against the wooden piles. Many ladies were distributing food, endeavoring to lead away the unfortunate negroes, but they refused to go. And the women would slowly shake their heads. One child of fourteen years of age had just been carried off to the hospital with his foot cut clean off at the ankle by an alligator. His family were howling with fury. They wished to keep the youngster with them. The negro quack doctor pretended that he could have cured him in two days and that the white quacks would leave him for a month in bed.

I left this city with regret, for it resembled no other city I had visited up to then. We were surprised to find that none of our party was missing though we had gone through—so they all said—various dangers. The hairdresser alone, a man called Ibé, could not recover his equilibrium, having become half mad from fear the second day of our arrival. At the theater he generally slept in the trunk in which he stored his wigs. However strange it may seem, the fact is quite true. The first night, everything passed off as usual, but during the second night he woke up the whole neighborhood by his shrieks. The unfortunate fellow had got off soundly to sleep, when he woke up with a feeling that his mattress, which hung over his collection of wigs, was being raised up by some inconceivable movements. He thought that some cat or dog had got into the trunk and he lifted up the feeble rampart. Two serpents were within, actively moving about, of a size sufficient to terrify the people that the shouts of the poor Figaro had caused to gather round.

He was still very pale when I saw him embark on board the boat that was to take us to our train. I called him and begged 432him to relate to me the odyssey of his terrible night. As he told me the story he showed me his heavy leg. “They were as thick as that, madame. Yes, like that....” And he quaked with fear as he recalled the dreadful girth of the reptiles. I thought that they were about one-quarter as thick as his leg, and that would have been enough to justify his fright, but the serpents in question were inoffensive water snakes that bite out of pure viciousness, but have no venom fangs.

We reached Mobile somewhat late in the day. We had stopped at that city on our way to New Orleans, and I had had a real attack of nerves caused by the “cheek” of the inhabitants who, in spite of the lateness of the hour, had got up a deputation to wait upon me. I was dead with fatigue and was dropping off to sleep in my bed on the car. I therefore energetically declined to see anybody. But these people knocked at my windows, sang about my carriage, and finally exasperated me. I quickly threw up one of the windows and emptied a jug of water on their heads. Women and men, among whom were several journalists, were splashed. Their fury was great.

I was returning to that city, preceded by the above story embellished in their favor by the drenched reporters. But on the other hand there were others who had been more courteous and had refused to go and disturb a lady at such an unearthly hour of the night. These latter were in the majority and took up my defense.

It was therefore in this warlike atmosphere that I appeared before the public of Mobile. I wanted, however, to justify the good opinion of my defenders and confound my detractors. Yes, but the Gnome who had decided otherwise was there.

Mobile was a city that was generally quite disdained by impresarii. There was only one theater. It had been let to the tragedian Barrett, who was to appear six days after me. All that remained was a miserable place, so small that I know of nothing that can be compared to it. We were playing “La Dame aux Camélias.” When Marguerite Gautier orders supper to be served, the servants who were to bring in the table 433ready laid tried to get it in through the door. But this was impossible. Nothing could be more comical than to see those unfortunate servants adopt every expedient.

The public laughed. Among the laughter of the spectators was one that became contagious. A negro of twelve or fifteen who had got in somehow was standing on a chair, and with his two hands holding on to his knees, his body bent, head forward, mouth open, he was laughing with such a shrill and piercing tone, and with such even continuity, that I caught it, too. I had to go out while a portion of the back scenery was being removed to allow the table to be brought in.

I returned somewhat composed, but still under the domination of suppressed laughter. We were sitting round the table and the supper was drawing to a close as usual. But just as the servants were entering to remove the table, one of them caught the scenery that had been badly adjusted by the scene shifters in their haste, and the whole back scene fell on our heads. As the scenery was nearly all made of paper in those days, it did not fall on our heads and remain there, but round our necks, and we had to remain in that position without being able to move. Our heads having gone through the paper, our appearance was most comical and ridiculous. The young negro’s laughter started again more piercing than ever, and this time my suppressed laughter ended in a crisis that left me without any strength.

The money paid for admission was returned to the public. It exceeded 15,000 francs.

This city had a fatality for me and came very near proving so during the third visit I paid to it.

That very night we left Mobile for Atlanta, where, after playing “La Dame aux Camélias,” we left again the same evening for Nashville.

We stayed for an entire day at Memphis and gave two performances. At one in the morning we left for Louisville.