I recently wrote a blog post on a poet with Alabama connections, Sara Henderson Hay. In the course of researching Hay, I discovered her relationship in the 1930's with another state author, Gladys Baker.

Here's what I wrote in that blog post about Baker: "In 1935 while at Scribner's Hay was able to tour Europe as secretary to Gladys Baker, a syndicated newspaper columnist. Baker had moved to the Magic City in 1926 to begin working for the Birmingham News. Small world, isn't it? I've yet to discover how the two women met, but on the tour they met with Pope Pius XI, Mussolini, Ataturk and other notables."

Unfortunately, I still haven't discovered how Hay and Baker met. Let's investigate.

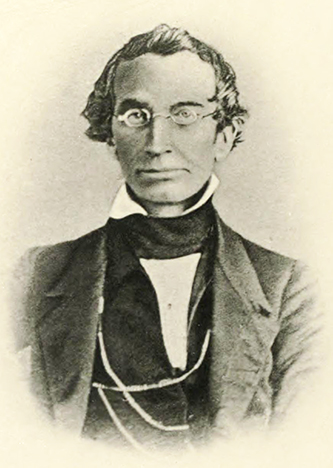

Baker was born around 1900 in Jacksonville, Florida. Despite a fair amount of searching, I have yet to find an exact date. Her parents were Arthur Herbert [1869-1926] and Johnnie Niblo Baker [1873-1936]. They were married on December 23, 1890, in Glenn, Georgia.

Before her death on December 18, 1957, Baker had published countless newspaper articles in papers around the world and two books. Her first book, I Had to Know, was published in 1951 and chronicles her life up to that point and her conversion to Catholicism and from a Southerner to a "Damyankee" in Vermont. She retired from newspaper writing in 1942.

She landed her first newspaper job at the Jacksonville Journal while in her late teens. According to the 1919 Jacksonville City Directory the family lived at 1849 Riverside Avenue, and her father worked as a clerk at the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company.

Her next job was at the Birmingham News Age-Herald, "where that great editor Charles A. Fell created a job for me--special New York correspondent." Her contract called for a full-page interview with a celebrity or newsmaker for the Sunday edition.

In her autobiography she tells us she soon moved to NYC and had her pieces appearing not only in the Birmingham paper but also publications in Dallas, Charlotte, Atlanta and Jacksonville. Before long she had national syndication. Baker met H.L. Mencken, who introduced her to fine dining at the 21 Club, downstairs where celebrities ate. "Our table was the mecca of the literati," she declared. Unfortunately, she does not name a single one of them. By this time Mencken had met, but not yet married Sara Haardt, an author and native of Montgomery, Alabama.

Baker often fails to offer names and dates. For instance, she discusses her childhood and parents, but does not give us their names! We learn them from the New York Times notice of her marriage to automotive executive Howard Coffin on June 2 1937: the late Mr. and Mrs. A. Herbert Baker of Jacksonville, Florida. The parents names also appear in Baker's "Alabama Authors" entry linked in the second paragraph. Strangely, Baker is not named in Coffin's Wikipedia entry; at any rate the marriage did not last long. He died later that year. Oh, and he's not mentioned in her book, either. She also didn't bother to name her four siblings.

She wrote two syndicated serial fiction stories, "Sallie's Temptations" and "Mr. and Mrs. Sallie" The first installment of "Sallie's Temptations" can be found in the Carbon County [Montana] News on January 8, 1925. Syndication to various newspapers had begun the previous year. Like so many such serials, neither was ever published in book form.

Baker had four husbands: William H. Oates, William H. Kellig, Jr., Howard E. Coffin and Roy Leonard Patrick.

Her first book, dedicated to her fourth husband, is mainly a record of two things: all the celebrities she interviewed during her newspaper career and her search for spiritual fulfillment that ends in Catholicism. One chapter also chronicles her battles with a mysterious illness in 1946. All well and good, but for my purposes very disappointing. There is little mention of her time in Birmingham or even the years she spent in Jacksonville. There is no mention at all of Sara Henderson Hay.

I have not read her novel, Our Hearts Are Restless, published in 1955. You can find her first book at the Internet Archive.

So my search for information about Hay in New York in the 1930's was fruitless. I did learn more about Baker, but she did not seem to be much interested in giving many details of her life before her conversion. Her connection with Alabama is also pretty slight. Another thing I found frustrating was the lack of information I found in census and other records about her parents and siblings.

That "Alabama Authors" entry on Baker gives as sources "files" at the Birmingham Public Library and the Alabama Department of Archives and History. Research at those two places might produced more details. I was also unable to view her obituary in the New York Times; it's behind their paywall.

Oh, well, you never know where these journeys down a rabbit hole will end up....

Published by Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1951

Baker may have been famous in her day, but she's forgotten now.

Source:

Files at Birmingham Public Library; Alabama Department of Archives and History; and from New York Times, December 18, 1957.

Publication(s):

I Had to Know. New York; Appleton Century, 1951.

Our Hearts Are Restless. New York; Putnam, 1955.