Wednesday, November 22, 2023

Auburn vs. Birmingham-Southern in 1938

Friday, November 17, 2023

Tennant S. McWilliams, PhD [1943-2023]

I wanted to note the passing on October 23 of UAB Professor Emeritus and historian Tennant S. McWilliams, who served as Dean of the School of Social Behavior and Sciences from 1990 until 2007. He graduated from Birmingham-Southern in 1965, then earned a master's at the University of Alabama in 1967 and a PhD from the University of Georgia in 1973. The following year he began his career at UAB, which lasted until retirement in 2010. During those years he had not only served as a dean, but in several other administrative posts at the university.

He published several books; three of them are noted below. I've found the UAB history very useful.

- Hannis Taylor: New Southerner as American. University of Alabama Press, 1978.

- The New South Faces the World: Foreign Affairs and the Southern Sense of Self. Louisiana State University Press, 1988. Paperback 2006.

- New Lights in the Valley: The Emergence of UAB. University of Alabama Press, 2008.

- The Chaplain’s Conflict: Good and Evil in a War Hospital. Texas A&M University Press, 2012.

- Dixie Heretic: The Civil Rights Odyssey of Renwick C. Kennedy. Forthcoming. University of Alabama Press, 2023.

Friday, November 10, 2023

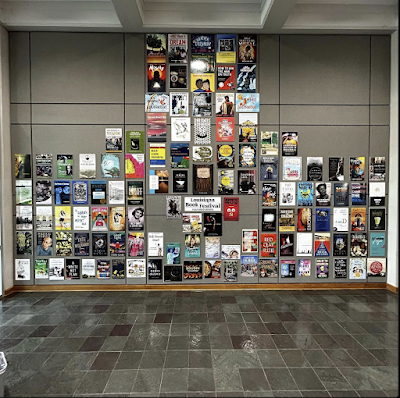

Alabama at the Louisiana Book Festival, 2023

On October 28 Dianne and I attended the Louisiana Book Festival in Baton Rouge. Our son Amos appeared on two panels as noted below in support of both his books, the new novel Petrochemical Nocturne and his 2018 collection of stories, Nobody Knows How It Got This Good. We were also at the 2018 festival shortly after his first book was published.

As you can see from the schedule below, this book festival is a one-day event packed with panels of authors, demonstrations of various sorts, and a massive book tent where signings and lots of purchases take place. Oh, and food trucks. Despite pretty warm weather, the event drew hordes of people, kids, and dogs.

The festival also attracts authors of all sort of books--fiction, non-fiction, poetry, memoirs, children's, cookbooks, etc. Naturally, Amos wasn't the only author with Alabama connections. Others included Kari Frederickson, a history professor at the University of Alabama and author of Deep South Dynasty: The Bankheads of Alabama, and prolific novelist Carolyn Haines, who was inducted into the Alabama Writers Hall of Fame in 2020. Novelist and freelance author Terah Shelton Harris and poet Rodney Jones also appeared.

You can read more about Amos and his writing here.

Friday, November 3, 2023

Ration Books in World War II

In the summer of 1941 rationing increased in the United Kingdom due to military needs and German attacks on shipping in the Atlantic. The government there asked the U.S. to conserve food, and the U.S. Office of Price Administration began warning Americans of potential shortages in gasoline, steel, and other areas. The OPA created a rationing structure after the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Local officials chose volunteers for 5500 ration boards around the country. A system of books and stamps given to individuals in families were used to obtain rationed goods. Some stamps specified the rationed product, others were later associated with other goods. For instance, one airplane stamp allowed a person to buy a pair of shoes; stamp number 30 from ration book four was needed for five pounds of sugar. Other strictly regulated products included tires, gasoline, meats, cooking oil, butter and canned goods. All household members received ration books, as did merchants of all types. As you might expect, a black market quickly developed. Read more details about U.S. rationing during World War II here.

Ration books were issued in four waves during the war. Book 1 came out in May 1942 and applied to sugar. In January 1943 Book 2 appeared with blue and red stamps. Blue covered canned goods, and red later went into use for meats, fish and dairy products. Book 3 in October 1943 utilized brown stamps for meats, canned milk, cheese, butter and lard. Book 4 had been issued in July and August 1943 with green stamps for processed foods such as canned, frozen or dried. Black stamps labelled "spare" were included for future use.

As if that weren't complicated enough, gas rationing was achieved with four types of use. Class A allowed 3-5 gallons a week for shopping, church, and doctor visits. Class B applied to factory workers and traveling salesmen, who received 8 gallons per week. Classes C [essential war workers, police, doctors, mailmen] and Class T [truck and bus drivers] had no restrictions.

Our family is blessed--some might say cursed--with all sorts of paper ephemera from past decades. The ration books shown here are examples. See more comments below.

Friday, October 27, 2023

A 1936 Check from Marion Bank & Trust

Friday, October 20, 2023

Lola Montez Visits Mobile in 1852

Lola Montez in 1851

In the first half of the nineteenth century "Lola Montez" was a famous--and notorious--dancer and actress who performed in Europe, the United States and elsewhere. She was born in Ireland on February 17, 1821, as Eliza Rosanna Gilbert. At the age of 16 she eloped to India with Thomas James, a lieutenant who became her first husband. They separated five years later, and Gilbert began her professional dancing career as Lola Montez.

In her short life Montez would have two other husbands and numerous lovers. That group included King Ludwig I of Bavaria, who gave her the title Countess of Landsfeld. In 1848 revolutions began in the German states, and Montez fled for Austria, Switzerland, France, London, and then America. She supported herself by dancing as she had earlier under the name Lola Montez.

Her career declined in the later 1850s. After a failed tour of Australia in 1855 and 1856, she returned to the U.S. by way of San Francisco. Further U.S. tours were unsuccessful, and she spent her final years in rescue work among "fallen" women and lecturing on morality. Montez died of syphilis on January 17, 1861, a month short of her 40th birthday, and was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

At the height of her fame she descended upon Mobile in December 1852. The Port City was not very large at the time, but had a lively performing arts scene and was a perfect stop for entertainers or theatrical companies appearing on tour in Charleston, South Carolina and New Orleans. Thus Mobile attracted Montez after appearances in Charleston that year.

Her venue was the Mobile Theatre, opened in 1841 and being operated at that time by Joseph Field, an actor, writer and theatrical manager. I've written about one of his publications, The Drama in Pokerville [1847], some of which is set in Wetumpka. Local newspapers expressed some trepidation about the appearance of Montez, but her visit was also highly anticipated. The Mobile Daily Register declared that "...the terror of the Jesuits, the favorite of an Emperor, and the cynosure of all eyes; will make her appearance on the Mobile state tomorrow evening...already we are impatient." Because of her lifestyle and her for-the-times erotic dancing, Montez was a controversial figure, but that didn't seem to prevent many people from attending her performances.

The arrival of Montez by the steamer Louisa was delayed, which no doubt increased the local anticipation. She gave six performances from December 21 and 28. Despite selling out the theater, Montez and Field had entertainment competition in Mobile. Horse races continued at the Trotting Club and Dan Rice's Hippodrome featured minstrel shows, circus acts and a parody of Hamlet.

The December 21 crowd included "a large number of highly enthusiastic ladies" who watched Montez in her "Sailor's Dance" and "Spider Dance". These performances came between various comedies from the theater's regular company. After two night of dances, a third night on December 23 featured "Lola Montez in Bavaria" with the lady enacting scenes from her own life. Christmas Eve repeated the drama, but added "Sailor's Dance".

On Christmas Day she played the title role in Maritana with Joseph Field as the male lead. Maritana was an opera written by William Vincent Wallace and first performed in London in 1845. Her final appearance on December 28 repeated "Lola Montez in Bavaria" and added the dance "La Saviglliana". On that final night the enthusiastic audience convinced her to repeat the dance. In a curtain call Montez expressed her appreciation of the response to her by audiences in Mobile. She left the city and arrived in New Orleans on New Year's Eve.

I want to express my appreciation to Sara Elizabeth Gotcher whose dissertation cited below provided many details and newspaper quotes about Montez's appearance in Mobile.

FURTHER READING

Burr, C. Chauncey. Autobiography of and Lectures by Lola Montez [1860]

Gotcher, Sara Elizabeth. "The Career of Lola Montez in the American Theatre" PhD dissertation, LSU, 1994

Morton, James, Lola Montez: Her Life & Conquests, Portrait, 2007

Seymour, Bruce, Lola Montez, a Life, Yale University Press, 1996

Photo by Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon