Celebrations of motherhood were practiced among ancient cultures, including the Greeks and Romans. A modern day to honor mothers is celebrated in many countries around the world, and the concept originated with Anna Jarvis in the United States early in the 20th century.

Born in West Virginia, Jarvis became a literary and advertising editor for an insurance firm in Philadelphia. When her mother Ann's health began to decline, she moved to Philadelphia so Anna could care for her. Ann died on May 9, 1905.

Various efforts to honor mothers had appeared in the United States in the 19th century. Ann Jarvis, who had nursed soldiers on both sides in the Civil War, had created Mother's Day Work clubs to work on public health issues after the war.

After her mother's death, Anna began a sustained campaign to create a Mother's Day. In 1910 her efforts started reaching fruition as West Virginia became the first state to officially recognize the second Sunday in May as Mother's Day. Alabama U.S. Senator J. Thomas Heflin wrote and achieved passage of a national recognition when Congress passed a law on May 8, 1914. The following day President Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation in support of Mother's Day. In 1934 President Franklin Roosevelt approved a stamp to honor the day.

By 1910 Alabama had also recognized Mother's Day. Below you can see a newspaper notice from May 1, 1910, that Governor B.B. Comer had issued a proclamation declaring Sunday, May 8, to be Mother's Day in Alabama. Just below that notice is another one about Comer, noting he had been kicked by a horse and would be unable to the upcoming World's Fair banquet to which the mayor of New York City had invited him.

Sentiments surrounding Mother's Day appeared in a 1926 issue of the Avondale Sun published for employees of the state's Avondale mills. The author of the letter, Charlie Harris, declared "And on Mother's Day you should send your mother something to make her happy."

Mother's Day in 1963 was not so happy for some people in Anniston. The article below notes that two homes of blacks and a black church were riddled with shotgun fire from a passing car in the afternoon. The homes were filled with people celebrating the day; the church was empty. Luckily no one was injured. In May 1961 Anniston had been rocked by violence during the Freedom Rides through Alabama.

By the early 1920's Mother's Day had been fully commercialized by the greeting card, floral and candy industries. For years Anna Jarvis unsuccessfully fought these changes; she felt the celebration should be about sentiment, not money. She spent her last years in some economic distress and finally in a sanitarium. She never married and never had children of her own.

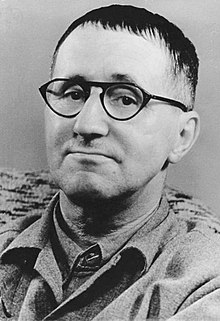

Anna Jarvis [1864-1948]

Source: Wikipedia

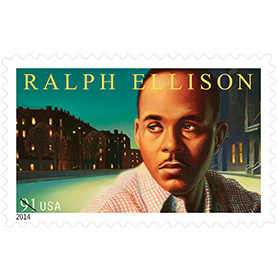

Source: Wikipedia

Source: Gadsden Times 12 May 1940

J. Thomas Heflin [1869-1951] was a U.S. senator from Alabama and held other positions during his long life. He was an ardent supporter of convict leasing and white supremacy and helped draft the state's infamous 1901 constitution.

Source: Pensacola Journal May 1, 1910, via the Library of Congress' Chronicling America digital collection. The same notice appeared in the Washington, D.C., Evening Star on the same date.