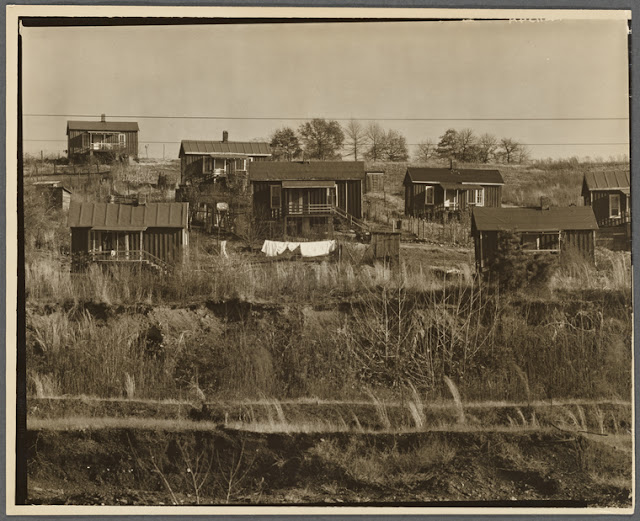

The article below written by Roland Harper appeared in 1922. As L.J. Davenport, the author of the Encyclopedia of Alabama article about him notes, "He was one of the last botanists to visit and describe the native vegetation of the Southeast before it was altered drastically by human activity." Harper documented his field trips with extensive notes and more than 7000 photographs.

He took a circuitous route to Alabama. Born in Maine, he lived with his family there and in Massachusetts while his father worked as a science teacher and school administrator. When Roland apparently came down with tuberculosis, the family moved to Georgia. He graduated from the University of Georgia in 1897 with a degree in engineering.

The family moved back to Massachusetts, and within a couple of years Harper had published his first botanical paper. He enrolled in Columbia University where he studied both botany and geology and received a PhD in 1905. In that same year he began working for the Geological Survey of Alabama and continued there until his 1966 death.

Over the course of his long career Harper published hundreds of items, including books and scientific papers. His major works include The Economic Botany of Alabama published in two parts in 1913 and 1928. Other works include Forests of Alabama [1943] and Preliminary Report on the Weeds of Alabama [1944].

Wikipedia has this to say about pine barrens:

"Pine barrens, pine plains, sand plains, or pinelands occur throughout the northeastern U.S. from New Jersey to Maine (see Atlantic coastal pine barrens) as well as the Midwest, Canada and northern Eurasia. Pine barrens are plant communities that occur on dry, acidic, infertile soils dominated by grasses, forbs, low shrubs, and small to medium sized pines."

Harper notes this botanical feature of pine forests in sand, gravel or clay stretching from Delaware into Alabama and Mississippi. These areas support bogs of typically unusual or rare plants. In Alabama Harper says the bogs are scarcer since the soil has more clay.

He describes his visits to a portion of these bogs in Autauga and Chilton counties in 1905 and 1921 respectively. Harper "examined quite a number of them" in Chilton County after noticing a pitcher plant from his train car. His article includes lists of woody plants and herbs including some not previously reported in the area.

The article by Davenport linked above gives more information about Harper's life and career. A book-length biography by Elizabeth Findley Shores is cited below. I am pleased to note that she is a relative!

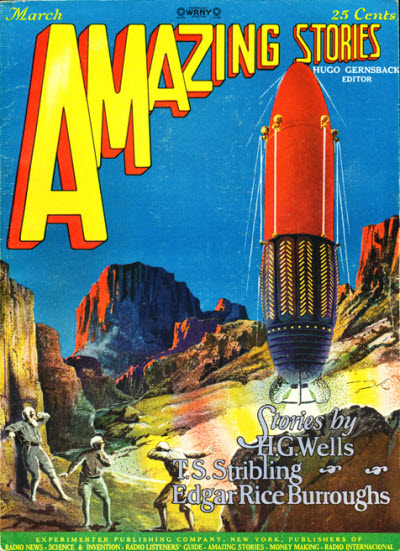

Torreya was a journal published under that title from 1901 until 1945 by the Torrey Botanical Society named after a professor at Columbia College in the mid-19th century. Harper's article can be found at the Internet Archive here.

Further Reading

Davenport, L. J. and G. Ward Hubbs. "Roland Harper, Alabama Botanist and Social Critic: A Biographical Sketch and Bibliography." Alabama Museum of Natural History Bulletin 17 (May 1995): 25-45

Shores, Elizabeth Findley. On Harper's Trail: Roland McMillan Harper, Pioneering Botanist of the Southern Coastal Plain. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2008

Roland Harper

Source: Encyclopedia of Alabama