Saturday, March 23, 2024

Movies with Alabama Connections: Bright Road

Saturday, March 16, 2024

Gadsden Postcard: Hotel Reich

Gadsden's Hotel Reich, built by Adolphe "Popo" Reich, opened on February 12, 1930. The ten-story structure had 150 rooms and interiors designed by Marshall Field's of Chicago. David O. Whilldin, a Birmingham architect active from 1902 until 1961, designed the hotel.

The Reich was meant to be first-class. Chefs were hired from New Orleans. After World War II big bands such as those of Guy Lombardo and Tommy Dorsey played the ballroom.

Popo's son Robert took over operations eventually, and the hotel was modernized in the 1960's. Sold in 1970, the new owner renamed it the Downtown Motor Hotel. In 1978 the facility was converted to the Daughette Towers subsidized housing for senior citizens.

This postcard, from my own collection, originated with E.C. Kopp, a printing and publishing company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, that operated from 1898 until 1956. Another Reich postcard can be seen here. Mike Goodson's article about the hotel's opening day is here. More information is available here.

Saturday, March 9, 2024

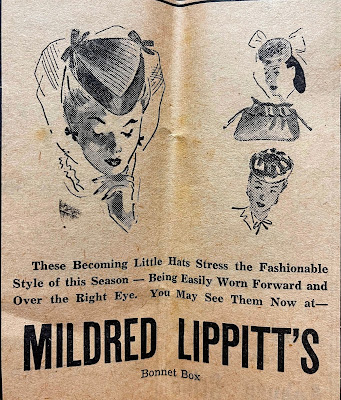

Ads in the Auburn Plainsman on February 7, 1945

I was recently sifting through a box of old newspapers that came from my paternal grandparents' house in Gadsden. I've written about them, Amos J. and Rosa Mae Wright, in a previous post and hope to do others in the future. This particular box of treasures contained mostly the front page section of many issues of the Gadsden Times published during World War II. I assume my grandmother saved them; she seemed to be the archivist of that couple. Naturally there is a lot of interesting war news, but the issues also have fascinating material from the Gadsden area and around the state and elsewhere. I imagine there are numerous possible blog posts buried there.....

But I digress. I also came across this random issue of the Auburn Plainsman, the university's student newspaper. My Dad, Amos J. Jr., was enrolled at Alabama Polytechnic Institute at this time, before a couple of years in the Navy just after the war ended. I didn't find too much of interest except some fascinating advertisements, so here we are.

The Plainsman had begun publication in 1922; you can find past issues here. The issue I found was six pages; the sheet with pages three and four is missing. I'm not sure why this random issue was saved, but perhaps Dad brought it home as a sample to show his mother while he was enrolled at Auburn.

I've made a number of comments below the ads, with help from these sources:

Ralph Draughon, Jr, et al. Lost Auburn: A Village Remembered in Period Photographs [2012]

Sam Hendrix, Auburn: A History in Street Names [2021]

War Eagle Theater was part of the Martin chain & the first chain theater in Auburn. This one must have been known as Martin Theater and later renamed.

By 1982 there were 300 Martin Theaters in the southeastern U.S. In that year the chain's owner, Fuqua Industries sold the chain to Carmike Cinemas. In 2016 Carmike was purchased by AMC Theatres.

This particular Martin opened on August 19, 1948 and closed in 1985. In October 1970 it hosted the first Alabama showing of I Walk the Line, based on the novel An Exile by Madison Jones [1925-2012], long-time faculty member at AU.

One of the films showing that I especially note and have enjoyed was To Have and Have Not, released in October 1944 and starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. The movie was based on Ernest Hemingway's 1937 novel.

I did not find anything about this establishment, even in a general Google search.

Friday, March 1, 2024

Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Passed the Test

I've written before on this blog about Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon, "the first certified, practicing female physician in Alabama". Dr. Dillon was a fascinating individual, the daughter of Benjamin Tanner, a prominent African-American minister in Pennsylvania and the sister of painter Henry O. Tanner. She graduated from the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1891, the only black in her class.

She was recruited by Booker T. Washington to become the physician at Tuskegee Institute, and she agreed. However, first she had to pass Alabama's certification exam, a grueling test that took place over several days and involved prominent white male physicians as examiners. At the time just a few black male doctors had passed the test and were practicing in Alabama. Washington arranged for her to be tutored by one of them, an old friend, Montgomery physician Cornelius Dorsette. She passed the test.

You can read more details about her life and career in the blog post I linked to in the first sentence. I've recently come across the two newspaper articles below that I have not seen before and which offer information about Dillon's examination.

The earliest and second one below is from the Washington Bee on October 3, 1891. That District of Columbia newspaper was primarily read by African-Americans. The article is actually a reprint, with no author give, from the Alabama Exchange. I have been unable to locate any information about that publication; perhaps it was a short-lived African-American paper in the state.

Booker T. Washington expected Dillon to start work at Tuskegee on September 1, so this article notes she "applied" to the state medical board on August 17. She took the exam in the state health office in Montgomery, "in which she was required to write the answers, without referring to any book of reference". Her answers were scored on ten different topics by ten examiners, all white male physicians. The testing ended August 25. See my previous blog post for more details.

Dillon made a total of 78.81 and a 75 minimum was required, the article states. She will teach anatomy and hygiene at Tuskegee in addition to her clinical duties. "She had a good literary education, having spent six years in college, writes a masculine hand, and it is stated that her examination was very creditable."

The second article by date [first one shown below], was published in the Capital City Courier in Lincoln, Nebraska. This piece has an attributed author, Lida Rose McCabe, a white journalist best known as the first female reporter to visit the gold fields in Alaska. Her article was filed from Philadelphia on November 5, and appeared in the Courier two days later.

"Alabama has now its first woman physician," McCabe wrote. Some of Dillon's background is included. Before her first marriage she worked as a bookkeeper for the Christian Recorder. Founded in 1852 by the African Episcopal Methodist Church, it is the oldest continuously published African-American newspaper in America. Her father was a minister in that church. "She spent her leisure hours reading medicine", McCabe wrote. She entered medical school after the death of her first husband. "Dr. Dillon was subjected to one of the severest ordeals" in state history--presumably state medical examination history, which had begun in 1877. McCabe notes the reluctance of the state's conservative medical professionals to admit black doctors unless "fully qualified". However, "Mrs. Dillon was courteously received."

McCabe states with no exceptions that Dillon was Alabama's first female physician. The earlier Bee article claims that Dillon was the first female certified by the state medical board, and that another female physician had been certified by the Jefferson County medical board at an earlier date. Under the 1877 law governing medical practice in Alabama, a candidate could take the exam either in Montgomery at the state board or before any county board. This arrangement allowed county medical societies to retain some power.

The white physician named as certified in Jefferson County was Anna M. Longshore [1829-1912]. Like Dillon, she came from a prominent family. Her father Joseph, a physician, helped establish the Woman's Medical College that Dillon would graduate from four decades later. Anna and her cousin Hannah were among the eight women in the first class of 1852.

Longshore did indeed take the exam in Jefferson County, but the Transactions of the Medical Association for 1892 [p.142] list her as "certificate refused." Thus Longshore may have been the first woman to take a certification exam in Alabama, but she did not pass. See my earlier post on Dillon for more about Longshore's long career as a physician and lecturer on medical topics. Why she came to Alabama to take the exam remains a mystery.

Another question is why Dillon took the exam in Montgomery and not in Macon County where Tuskegee Institute is located. Perhaps Washington and Dorsette wanted her to attempt the test in the state capital, before prominent white physicians, where a successful effort would receive more attention.

As I noted in my original blog post on Dr. Dillon, she "was not the first female physician in Alabama, but the first to be certified by the state examination process under the law passed in 1877. In the 1850s Louisa Shepard graduated from her father's medical school in Dadeville, the Graefenberg Medical Institute. The school closed in 1861 after graduating some 50 students, including two of Louisa's brothers. She never practiced medicine; she married William Presley and they moved to Texas. Louisa died in 1901."

via Chronicling America

Friday, February 23, 2024

Zora Neale Hurston's Letter to William Stanley Hoole

As one does now and then, I was recently glancing through Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters, collected and edited by Carla Kaplan and published in 2002. So what should I find but a letter with an interesting Alabama connection. Let's investigate.

I'm not going to say much about Hurston, who's life and career are well known. Her entry in the Encyclopedia of Alabama will give you the basics. Although born January 7, 1891 in Notasulga, she and her family soon moved to Eatonville, an all-black town in Florida. During the course of her life, she worked at odd jobs, wrote stories and essays, and did folklore field research in New Orleans, Florida, and Alabama. In the 1950s, she had a connection with another Alabama author, William Bradford Huie. See the Encyclopedia article for more details.

Hurston's final decade were filled with financial and health worries, and after moving back to Florida she worked as a maid. After a stroke in 1959 she entered a nursing home and died there on January 28, 1960. She was practically forgotten despite her substantial research and publication records. Author Alice Walker located her unmarked grave and published an article in 1975 that revived interest in Hurston's work.

William Stanley Hoole [1903-1990] had a long career as librarian and historian. Born in South Carolina, he finished his doctorate in English at Duke University and then taught first at what is now Jacksonville State University and then Birmingham-Southern. He left there for Baylor University and then what is now the University of North Texas,. In 1944 he became director of libraries at the University of Alabama, a post he held for 27 years. During that time he led tremendous growth of the libraries and archives there; the special collections were named after him in 1977.

Hoole wrote or edited 50 books, over 100 articles and numerous book reviews. His career encompassed significant achievements in the fields of both librarianship and history. He helped establish the Alabama Historical Association and edited its journal from 1948-1967. Subjects of his writing ranged from aspects of librarianship to Confederacy topics.

He seems to have written Hurston and other authors inquiring about their current projects and asking for a paragraph describing them. I've yet to determine if these were collected in any of his publications.

Hurston writes from New York City on March 7, 1936, to Hoole at Birmingham-Southern College. Her first paragraph is an explanation and apology. "I think I must be God's left-hand mule, because I have to work hard. That's very funny too, because no lazier mortal ever cried for breath. But the press of new things, plus the press of old things yet unfinished keep me on the treadmill all the time." Thus she hasn't answered his "kind and flattering letter before now."

The project Hurston describes is Their Eyes are Watching God which was published the following year. Then she tells Hoole, "I am glad in a way to see my beloved southland coming into so much prominence in literature. I wish some of it was more considered. I observe that some writers are playing to the gallery."

As she ends her letter Hurston describes some of the southern authors she admires, such as Erskine Caldwell, who wrote numerous novels including God's Little Acre, and Carl Carmer for his work Stars Fell on Alabama. She gives special praise to an Alabama writer. "T.S. Stribling is a monnyark, that's something like a king you know, only bigger and better. I love him."

Stribling wrote 16 novels and numerous articles and short stories. A trilogy of novels was set around Florence from antebellum times into the twentieth century; one of those, The Store, won a Pulitzer Price for fiction in 1933.

Her final words? "P.S. I come of an Alabama family. Macon County."

Saturday, February 17, 2024

Birmingham Photo (87): Rush Hotel in 1931

According to its entry at the great BhamWiki site, this hotel was developed by D.M. Rush around 1919 and operated until about 1949. The 1945 Birmingham Yellow pages gives its address as 316 1/2 North 18th Street and the phone number was 7-09411. The small hotel occupied just the second floor of the building seen in the photo below, and was one of the few such accommodations available to blacks in the city.

In the 1930's the facility was owned by Tom Hayes. The place apparently provided hotel arrangements for visiting teams in town to play the Birmingham Black Barons, which played professional baseball in the Negro leagues from 1919 until 1960. In his book Black Baseball's Last Team Standing: The Birmingham Black Barons, 1919-1962 [2019], Bill Plott has a couple of tidbits about the hotel. Manager of the Barons in 1938 was William "Dizzy" Dismukes, a Birmingham native who had also managed the team in 1924. Anyone who wanted to try out for the team that year could contact him at the Rush Hotel [p.117]. He also writes that in 1953 Dismukes had set up shop again at the hotel, this time to recruit for the New York Yankees [p.221]. Thus the hotel may have operated past 1949.

A man named Joe Rush was Black Barons owner in 1923 and 1924, and owner and president in 1925. The Birmingham Black History Project on Facebook has more information about the Rush family.

Below I've also included a photo from Google Street View showing what the building looked like in 2019.

Photo by W.B. Phillips in 1931

Source: Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

Here's the building via Google Street View February 2019. You can see the same arch over the doorway and the eight windows in the second story.