On a recent trip to visit our daughter, son-in-law and grandson in the Jacksonville, Florida, area, Dianne and I stopped at a cemetery beside the St.Luke's Episcopal Church in Marianna. We do that sort of thing in our family. Daughter Becca visited her brother Amos in New Orleans recently, and the first photo she texted showed them in one of the city's spectacular cemeteries. Blog posts I've written about cemetery visits include--but are not limited to-- Allan Cemetery in northern Shelby County, the Pelham cemetery, and Harmony Graveyard in Helena.

But the wife and I had a specific reason for stopping at St. Luke's. Caroline Lee Hentz, one of America's best selling antebellum authors, and many of her family members are buried there. Hentz and her husband Nicholas, accompanied by their children had spent a decade and a half in Alabama operating private schools in various cities. So let's look into this situation.

In 2014 I published a blog post on Marie Layet Shiep, a Mobile native and author who died in Apalachicola. She had a fascinating career as well, which included script writing for early silent films and publication of a controversial novel, Gulf Stream, set in Mobile. She is buried in that city, but I'm sensing a theme of interest here--authors with both Alabama and Florida connections. Zora Neale Hurston, anyone?

Caroline Lee Whiting was born in Lancaster, Massachusetts, on June 1, 1800, the youngest of eight children. Her father John was a bookseller. At 17 she began teaching in a local school, and seven years later married Nicholas Hentz, a French native who came to America in 1816 with his family after the fall of Napoleon.

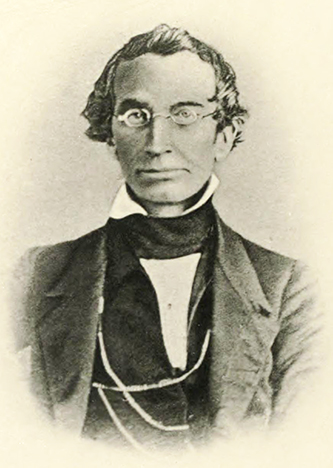

At the time of their marriage, Hentz was teaching at the Round Hill School in Northampton. He had studied medicine and miniature painting in France and in America expanded his interests to include the study of spiders; his manuscript on that topic was published posthumously in 1875. Hentz also suffered from serious bouts of depression and jealousy throughout his life; these emotional states may have been behind the family's tendency to move every few years.

As noted in the chronology below, the Hentzes lived in Massachusetts, North and South Carolina, Kentucky and Ohio before ending up in Alabama. Apparently an episode of jealousy by Nicholas led him to move the family from Cincinnati to Florence, Alabama. Hentz later used this family drama in her fictional accounts of male jealousy.

The Hentzes were in Florence from late 1834 until 1843, the longest period the family ever lived in one place. Caroline kept a diary for 1836, their second full year in the state. That manuscript is in the Southern History Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. The finding aid for the Hentz Family papers there can be found here.

Their home and schoolhouse was a two-story white-washed brick cottage she named Locust Dell. The first floor was a large teaching room; dormitories for pupils were upstairs. Nicholas constructed a square building in the yard for the pianos and music instruction. Hentz had her own four children and 15-20 boarding students plus 60-100 day students to manage at Locust Dell.

Hentz describes in her diary a range of emotions we might expect from a stranger in a strange land. She is homesick for both the Massachusetts of her youth and the friends she left in Cincinnati that she misses.

The pleasures and frustrations of running a private school are clear. On May 30 she has to treat her students with "Alternate coaxing and scolding, counsel and reproof, frowns and smiles--Oh, what a life it is. Oh woe's me--this weary world, I am oft tempted to say." Then, on June 6, "The last week of the session. Welcome sweet season of rest." And the next day, "Arithmetic, for the last time this session. Rejoice."

She also talks about July 4 celebrations, at that time a serious business of readings and speeches. She, Nicholas and the children made summer fishing trips to the Coffee plantation north of Florence. General John Coffee, who served under Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812, had died in 1833, but his widow and children still lived on the property. Two of the sons were among the few boys enrolled at the Hentzes' school. During these trips samples were collected for Nicholas' insect collection.

Her leisure reading that year included the poetry of Lord Byron and fiction by Frederick Marryat, Edward Bulwar-Lytton and Maria Edgeworth. The arrival of books by steamboat was a cause for family celebration.

The year's diary is filled with observations about the rich natural world around her. In February 1836 Hentz declares the snows of New England have lost their charms to the more "genial clime" of her new home. In various entries she notes the birds, nighttime stars, and many plants such as ranunculus, yellow narcissus and rosemary.

Nicholas published one novel, Tadeuskund, the Last King of Lenape in 1825. Also In 1825 Nicholas published an article in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society about the North American alligator. i wonder if he had ever seen one in the wild? He does say he had dissected several large specimens soon after they died while he was in South Carolina.

The couple had five children; Wikipedia summarizes: "Marcellus Fabius (1825–1827), Charles Arnould (1827–1894), Julia Louisa (1829–1877), Thaddeus William Harris(1830–1878), and Caroline Therese (1833–1904). Julia was born at Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She was educated by both of her parents and married in 1846 to Dr. John Washington Keyes in Tuskegee.[4] Julia wrote several short poems but most of her works were never published. Her most well known work was a prize poem called "A Dream of Locust Dell".[5] The youngest daughter, Caroline Therese was born in Cincinnati, Ohio and also educated by her parents and married the Baptist pastor, Rev. James O. Branch. She went on to publish tales and sketches published in magazines. Charles Arnould became a physician."

The Hentzes would end up spending fifteen years in Alabama operating private schools in several different towns. Caroline, a northerner by birth, became a southerner during that time and wrote several best selling novels about life in the South. When they arrived Alabama was still a frontier state; conditions were little changed by the the time she died except the Native Americans had been removed and the white and black populations had expanded.

Hentz (and often Caroline) taught at schools in these places after their marriage:

1824-26: school in Northampton, Mass.

1826-1830: UNC Chapel Hill as Chair of modern languages and belles lettres

1830-32: school in Covington KY

1832-34: Cincinnati

1834-43: Florence, Ala.

1843-45: Tuscaloosa

1845-48: Tuskegee

1848-ca. 1850: Columbus, Ga.

ca. 1850-1856: Marianna, Fla.

Caroline and Nicholas eventually moved in with son Charles the doctor in Marianna due to Nicholas' failing health. She wrote and published eight novels and seven story collections there to support the family before her death on February 11, 1856, of pneumonia. Her husband died on November 4 of the same year. Nathaniel Hawthorne probably would have included her in the "damned mob of scribbling women" he complained about in an 1855 letter to his publisher. In her final novel Ernest Linwood [1856], she explored such autobiographical themes as jealousy and the conflict between professional female authorship and domestic duties.

At the time of their marriage, Hentz was teaching at the Round Hill School in Northampton. He had studied medicine and miniature painting in France and in America expanded his interests to include the study of spiders; his manuscript on that topic was published posthumously in 1875. Hentz also suffered from serious bouts of depression and jealousy throughout his life; these emotional states may have been behind the family's tendency to move every few years.

As noted in the chronology below, the Hentzes lived in Massachusetts, North and South Carolina, Kentucky and Ohio before ending up in Alabama. Apparently an episode of jealousy by Nicholas led him to move the family from Cincinnati to Florence, Alabama. Hentz later used this family drama in her fictional accounts of male jealousy.

The Hentzes were in Florence from late 1834 until 1843, the longest period the family ever lived in one place. Caroline kept a diary for 1836, their second full year in the state. That manuscript is in the Southern History Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. The finding aid for the Hentz Family papers there can be found here.

Their home and schoolhouse was a two-story white-washed brick cottage she named Locust Dell. The first floor was a large teaching room; dormitories for pupils were upstairs. Nicholas constructed a square building in the yard for the pianos and music instruction. Hentz had her own four children and 15-20 boarding students plus 60-100 day students to manage at Locust Dell.

Hentz describes in her diary a range of emotions we might expect from a stranger in a strange land. She is homesick for both the Massachusetts of her youth and the friends she left in Cincinnati that she misses.

The pleasures and frustrations of running a private school are clear. On May 30 she has to treat her students with "Alternate coaxing and scolding, counsel and reproof, frowns and smiles--Oh, what a life it is. Oh woe's me--this weary world, I am oft tempted to say." Then, on June 6, "The last week of the session. Welcome sweet season of rest." And the next day, "Arithmetic, for the last time this session. Rejoice."

She also talks about July 4 celebrations, at that time a serious business of readings and speeches. She, Nicholas and the children made summer fishing trips to the Coffee plantation north of Florence. General John Coffee, who served under Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812, had died in 1833, but his widow and children still lived on the property. Two of the sons were among the few boys enrolled at the Hentzes' school. During these trips samples were collected for Nicholas' insect collection.

Her leisure reading that year included the poetry of Lord Byron and fiction by Frederick Marryat, Edward Bulwar-Lytton and Maria Edgeworth. The arrival of books by steamboat was a cause for family celebration.

The year's diary is filled with observations about the rich natural world around her. In February 1836 Hentz declares the snows of New England have lost their charms to the more "genial clime" of her new home. In various entries she notes the birds, nighttime stars, and many plants such as ranunculus, yellow narcissus and rosemary.

Nicholas published one novel, Tadeuskund, the Last King of Lenape in 1825. Also In 1825 Nicholas published an article in the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society about the North American alligator. i wonder if he had ever seen one in the wild? He does say he had dissected several large specimens soon after they died while he was in South Carolina.

The couple had five children; Wikipedia summarizes: "Marcellus Fabius (1825–1827), Charles Arnould (1827–1894), Julia Louisa (1829–1877), Thaddeus William Harris(1830–1878), and Caroline Therese (1833–1904). Julia was born at Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She was educated by both of her parents and married in 1846 to Dr. John Washington Keyes in Tuskegee.[4] Julia wrote several short poems but most of her works were never published. Her most well known work was a prize poem called "A Dream of Locust Dell".[5] The youngest daughter, Caroline Therese was born in Cincinnati, Ohio and also educated by her parents and married the Baptist pastor, Rev. James O. Branch. She went on to publish tales and sketches published in magazines. Charles Arnould became a physician."

The Hentzes would end up spending fifteen years in Alabama operating private schools in several different towns. Caroline, a northerner by birth, became a southerner during that time and wrote several best selling novels about life in the South. When they arrived Alabama was still a frontier state; conditions were little changed by the the time she died except the Native Americans had been removed and the white and black populations had expanded.

Hentz (and often Caroline) taught at schools in these places after their marriage:

1824-26: school in Northampton, Mass.

1826-1830: UNC Chapel Hill as Chair of modern languages and belles lettres

1830-32: school in Covington KY

1832-34: Cincinnati

1834-43: Florence, Ala.

1843-45: Tuscaloosa

1845-48: Tuskegee

1848-ca. 1850: Columbus, Ga.

ca. 1850-1856: Marianna, Fla.

Caroline and Nicholas eventually moved in with son Charles the doctor in Marianna due to Nicholas' failing health. She wrote and published eight novels and seven story collections there to support the family before her death on February 11, 1856, of pneumonia. Her husband died on November 4 of the same year. Nathaniel Hawthorne probably would have included her in the "damned mob of scribbling women" he complained about in an 1855 letter to his publisher. In her final novel Ernest Linwood [1856], she explored such autobiographical themes as jealousy and the conflict between professional female authorship and domestic duties.

Two of Caroline's children also did a bit of writing. The couple's youngest child Caroline Therese was born in Cincinnati in November 1833. She married a Methodist minister, Rev. James O. Branch. While living in California she wrote letters that were published in the Southern Christian Advocate in 1875. She also published tales and sketches in other magazines. She died in October 1904 and is buried in Georgia.

The older daughter Julia Louise had been born in North Carolina in October 1828. In 1846 she married John Washington Keyes while the family lived in Tuskegee. Keyes, a native of Athens, Alabama, was a physician who later studied dentistry. He served as a surgeon in the 17th Alabama Regiment in the Civil War. They lived in Florida at first, then moved to Montgomery in 1857. After the war Julia and her husband joined the Southerners who left the United States for Brazil. The pair and their children lived in the Gunter Colony from 1867 until 1870, when they returned to Montgomery. The family settled in Wewahitchka, Florida, where she died in 1877. She and John are both buried in Jehu Cemetery in that small Panhandle town. You can read more about the experiences of the Confederados in Brazil here and here.

Before and after her marriage Julia wrote poetry, most of which was not published. Appleton's Cyclopaedia of American Biography [1892] notes, "In 1859 Mrs. Keyes wrote a prize poem entitled 'A Dream of Locust Dell.' A selection of her poems was published by her husband." I have been unable to locate that collection, unless it's the one published as Poems in Brazil in 1918, some years after his death. Julia's memoir about their time in South America, "Our Life in Brazil" was published in the Alabama Historical Quarterly in 1966.

Charles A. Hentz was the oldest child who survived to adulthood. He was born in 1827 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and died in Quincy, Florida, in 1894. Along with Thaddeus, Charles was the other physician among the Hentz children; he practiced in the small Florida panhandle towns of Marianna and Quincy for his entire career. Charles began a diary at the age of 18, when the family was living in Tuscaloosa. The diary includes much about his life and medical practice; near the end of his life he also wrote an autobiography. These were published in 2000 as A Southern Practice: The Diary and Autobiography of Charles A. Hentz, M.D., edited by Steven M. Stowe; they make fascinating reading.

More text continues below the photos.

Hentz was inducted into Florence's "Walk of Honor" in 2007.

This cemetery marker notes the presence of other notables from the area in addition to the Hentzes.

A view across the cemetery with the church in the background

Thaddeus W. Hentz [1830-1878], was a son of Caroline and Nicholas; I've seen references to him as either a doctor or dentist.

Another view with the new church buildings in the background

Thaddeus W. Hentz [1860-1927], presumably a grandson

Grave of Caroline Lee Hentz [1800-1856]

The photo at Find-A-Grave shows the column atop its base; you can see the monument's condition when we were there below.

A single stone is inscribed as follows:

Children of Dr. John W. & Julia L. Keyes

Julia Hentz [11 Feb 1849 6 Dec 1849]

Infant boy [born & died 15 Dec 1853]

Henry Whiting [19 Sept 1851 4 Nov 1856]

The snapped rose usually indicates a young lady who died too soon, in this case young Julia.

Caroline Hentz's gravestone showing the column that has toppled

Cemetery view across Hentz's grave with the church in the background

Nicholas Marcellus Hentz

During his lifetime Hentz published numerous articles on spiders in scientific journals, as well as textbooks and other items.

Source: Wikipedia

Hentz was able to collect many more species of spiders during his years in the South than he had in the Northeast or Midwest. His collection of spiders and other insects was donated to a Boston museum. This book was published after his death.

Caroline Hentz's numerous novels and story collections are available via the Internet Archive. Her best known novel was The Planter's Northern Bride, published in 1854. The book is one of many that responded to Harriet Beecher Stowe's portrayal of slavery and the South in Uncle Tom's Cabin. As she observes in her introduction, Hentz had lived in Carolina, Alabama, Georgia and Florida and her own "northern bride" experience and observations were different from Stowe's. See below for an excerpt from that introduction. She felt her many years in the South gave her a truer picture of slavery than Stowe's. In one of those ironies of history, Hentz and Stowe had been members of the same literary society in Cincinnati.

Hentz was one of a number of antebellum female authors writing "domestic fiction" largely designed to instruct young women of the upper classes how to conduct themselves as adults in their proper sphere, the home. Most of her writing fits this general template. Contemporary scholars have noted that although the heroines don't ultimately overturn any social norms, they often spend much of these novels challenging the menfolk in various ways. Hentz's novels were popular into the 1890's, but have not been reprinted, and she is pretty much unknown to all but specialist scholars. You can see some of that scholarship here.

In addition to slavery, in her novels and stories Hentz explored courtship and marriage, uncontrolled emotions in both men and women, and the conflict between domestic duties and female literary achievement. She defended female intellectual capabilities and pursuits, but not at the expense of her role in the home.

In addition to slavery, in her novels and stories Hentz explored courtship and marriage, uncontrolled emotions in both men and women, and the conflict between domestic duties and female literary achievement. She defended female intellectual capabilities and pursuits, but not at the expense of her role in the home.

Hentz's response to Stowe put her into the "public sphere" where supposedly only the men operated. Of course, the same could be said for other female writers who responded to Stowe, as well as Stowe herself and those who agreed with her. Slavery was that kind of issue.

Her apologia for slavery renders Hentz's best known work highly problematic. As you can see in the photos above of the graves of her and her family, her final resting place seems as decayed as those ideas.

Press Notices

Published in The Planter's Northern Bride

Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson, 1854

READ WHAT SOME OF THE LEADING EDITORS SAY OF IT:"It is unquestionably the most powerful and important, if not the most charming work that has yet flowed from her elegant pen; and though evidently founded upon the all-absorbing subjects of slavery and abolitionism, the genius and skill of the fair author have developed new views of golden argument, and flung around the whole such a halo of pathos, interest, and beauty, as to render it every way worthy of the author of 'Linda,' 'Marcus Warland,' 'Rena,' and the numerous other literary gems from the same author." — American Courier. "We have seldom been more charmed by the perusal of a novel; and we desire to commend it to our readers in the strongest words of praise that our vocabulary affords. The incidents are well varied; the scenes beautifully described; and the interest admirably kept up. But the moral of the book is its highest merit. The 'Planter's Northern Bride' should be as welcome as the dove of peace to every fireside in the Union. It cannot be read without a moistening of the eyes, a softening of the heart, and a mitigation of sectional and most unchristian prejudices." — N. Y. Mirror. "The most delightful and remarkable book of the day." — Boston Traveler. "The characters are finely drawn, and well sustained, from the beginning to the end of the work." — Boston Morning Post. "Written with remarkable vigor, and contains many passages of real eloquence. We heartily commend it to general perusal." |

From Hentz's introduction:

We believe that there are a host of noble, liberal minds, of warm, generous, candid hearts, at the North, that will bear us out in our views of Southern character, and that feel with us that our national honour is tarnished, when a portion of our country is held up to public disgrace and foreign insult, by those, too, whom every feeling of patriotism should lead to defend it from ignominy and shield it from dishonour. The hope that they will appreciate and do justice to our motives, has imparted enthusiasm to our feelings, and energy to our will, in the prosecution of our literary labour.

When we have seen the dark and horrible pictures drawn of slavery and exhibited to a gazing world, we have wondered if we were one of those favoured individuals to whom the fair side of life is ever turned, or whether we were created with a moral blindness, incapable of distinguishing its lights and shadows. One thing is certain, and if we were on judicial oath we would repeat

it, that during our residence in the South, we have never witnessed one scene of cruelty or oppression, never beheld a chain or a manacle, or the infliction of a punishment more severe than parental authority would be justified in applying to filial disobedience or transgression. This is not owing to our being placed in a limited sphere of observation, for we have seen and studied domestic, social, and plantation life, in Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. We have been admitted into close and familiar communion with numerous families in each of these States, not merely as a passing visiter, but as an indwelling guest, and we have never been pained by an inhuman exercise of authority, or a wanton abuse of power.

On the contrary, we have been touched and gratified by the exhibition of affectionate kindness and care on one side, and loyal and devoted attachment on the other. We have been especially struck with the cheerfulness and contentment of the slaves, and their usually elastic and buoyant spirits. From the abundant opportunities we have had of judging, we give it as our honest belief, that the negroes of the South are

the happiest labouring class on the face of the globe; even subtracting from their portion of enjoyment all that can truly be said of their trials and sufferings. The fugitives who fly to the Northern States are no proof against the truth of this statement. They have most of them been made disaffected by the influence of others-- tempted by promises which are seldom fulfilled[.] Even in the garden of Eden, the seeds of discontent and rebellion were sown; surely we need not wonder that they sometimes take root in the beautiful groves of the South.

Hentz's death on February 11, 1856, at the home of her son Charles in Marianna, was widely covered by the American press. This item from an Ohio newspaper reprints an article from the New York Tribune.

Perrysburg Journal [Ohio] 1 March 1856

Source: Library of Congress Chronicling America

Even at least one anti-slavery publication covered her death; this one's author includes a description by someone who met Hentz. This article also includes a lengthy account of Hentz's return to Massachusetts in 1854 to visit relatives.

Anti-Slavery Bugle [Ohio] 29 March 1856

Source: Library of Congress Chronicling America

Works by Hentz

Lovell’s Folly (1833)

De Lara, or, The Moorish Bride (1843)

Aunt Patty’s Scrap-bag (1846)

Linda or, The Young Pilot of the Belle Creole (1850)

Rena, or, The Snow Bird (1851)

Eoline; or, Magnolia Vale; or, The Heiress of Glenmore (1852)

Ugly Effie, or, the Neglected One and the Pet Beauty (1852)

Marcus Warland, or the Long Moss Spring (1852)

Wild Jack, or the Stolen Child (1853)

The Planter’s Northern Bride (1854)

The Banished Son and Other Stories of the Heart (1856)

Courtship and Marriage (1856)

Ernest Linwood; Or, the Inner Life of the Author (1856)

The Lost Daughter and Other Stories of the Heart (1857)

FURTHER READING

Beidler, Philip D. Caroline Lee Hentz's Long Journal. Alabama Heritage winter 2005, pp. 24-31

Beidler, Philip D. Caroline Lee Hentz's Long Journal. Alabama Heritage winter 2005, pp. 24-31

Ellison, Rhoda Coleman. Mrs. Hentz and the Green-Eyed Monster. American Literature 22: 345-350, November 1950

Ellison, Rhoda Coleman. Caroline Lee Hentz's Alabama Diary. Alabama Review 4: 254-269, October 1951

Horn, Patrick E. The Literary Friendship of George Moses and Caroline Lee Hentz. North Carolina Literary Review 28: 134-143, 2019 [Moses was an enslaved poet.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)